Creative Financing in the NBA, 2011

January 20th, 2012

|

| The only beardless picture of Rashard Lewis I could find. It’s a part of him now. |

“Creative financing.” A fun term, one that’s actually employed by financiers and accountants, yet one brought into the world of the NBA when it was used, once, in a pre-emptive justification for one of the least creatively financed transactions of a generation. Nevertheless, even if the man who gave reverence to the phrase isn’t the role model for its usage, creative financing does exist in the NBA.

Or at least, it did.

In amongst the lockout, the protracted negotiations, and the almost complete loss of a season/confidence in the NBA’s product, a new Collective Bargaining Agreement was drawn up that sought to curb spending, introduce more payroll parity, and get the league back into the black.

For those of us who enjoy looking at, and looking for, means to creatively manipulate, it was a confusing time.

Of course, some teams acted like nothing had happened. Detroit gave $25.5 million to Rodney Stuckey to come back, gave $18 million to Jonas Jerebko to come back, gave $28 million to Tayshaun Prince to come back, and gave $14.5 million to Rip Hamilton to go away, committed as they were to retaining the core of a team that’s gone 57-107 over the last two seasons. Meanwhile, Philadelphia spent only what it cost to re-sign Thaddeus Young and replace Darius Songaila with Nikola Vucevic; hamstrung as they were by incumbent contracts, the team had too little wiggle room to do very much, something which will likely continue to be the case for the final 18 months of the Elton Brand era.

Most others, however, recognised the changing environment, and were willing (or able) to adapt accordingly.

Perhaps the most prominent example of this is the defending champion, Dallas Mavericks. Dallas won the title last year because of two factors – Dirk Nowitzki and their incredible depth. This offseason, however, they dismantled the latter. This was a team so deep that players like Corey Brewer and Roddy Beaubois – who, lest we forget, had a 40 point game as a rookie – spent their time getting DNP-CD’d. And yet this winter, it was all let go. Historically the biggest of all the spenders, Dallas has been profoundly cutting payroll, with an eye to being under the cap for the first time in the Mark Cuban era. With Jason Kidd and Jason Terry aged and expiring, the Mavericks front office have decided to go from old to young, and from expensive to cheap (rentals of Lamar Odom and Vince Carter notwithstanding). So emphatic have they been in the pursuit of salary savings that they traded away a player they had acquired just that draft night for the cost a first-round pick (and potential steal of the draft, Jordan Hamilton), salary dumping onto the Nuggets before so much as letting him practice with them. When the new rules came in, Dallas’s old plan went out.

Rightly or wrongly, the Mavericks devised a strategy and are working towards it. A perennial tax paying team are not likely to be so any longer. Indeed, in the early going, the NBA’s aim of reducing spending on payroll is working charmingly, as evidenced by its potential luxury tax payers. Or lack of them.

As of the time of writing, seven NBA teams stand to be taxpayers this season.

– L.A. Lakers, $87,865,859 ($17,558,859 over)

– Boston, $79,297,502 ($8,990,502 over)*

– Miami, $78,023,431 ($7,716,431 over)*

– Dallas, $74,825,424 ($4,518,424 over)

– San Antonio, $74,013,155 ($3,706,155 over)*

– Memphis, $71,438,001 ($1,131,001 over)

– Atlanta, $71,203,605 ($896,605 over)*

[* = players with less than two years experience that are signed to the minimum salary are, for luxury tax purposes only, counted as having the minimum salary of a two year veteran/third year player. Therefore, Greg Stiemsma’s $762,195 salary and cap hit is treated as $854,389 for tax calculations, and only for tax calculations. The same is true of the first- or second-year minimum salaries being paid to Mickell Gladness and Terrel Harris of Miami, Donald Sloan and Ivan Johnson of Atlanta, and Gary Neal and Malcolm Thomas of San Antonio, hence the deviation between the above figures and the salary charts they link to.]

Even after trading Lamar Odom, the Lakers have no chance of getting under the luxury tax. Indeed, they never did – they traded Odom to alleviate some of the burden, not to completely remove it. Boston has similarly little chance, barring being part of a far larger roster upheaval, which isn’t entirely impossible. Miami doesn’t want or need to, and San Antonio, by not amnestying Richard Jefferson, have made it very unlikely that they’ll manage to dip back under. Nevertheless, with comparatively few teams over by comparatively little margins, we are barely a few months into the tougher luxury tax era and yet we’re already seeing less big spending then before. If this was what the owners wanted, it seems as though they’re going to get it.

Making the teams who can afford to spend more, spend less, doesn’t seem to address the NBA’s core problem of teams who struggle to stay in the black even at minimum payroll levels. But that’s an argument for another day.

|

| Tyler Hansbrough, thinking of victims. |

There’s also leftover cap space. Quite a lot of it, in fact.

At the bottom of the pile are the Indiana Pacers. Finally free from the payroll problems that have plagued them since the Brawl at the Palace, the Pacers entered the offseason with more cap space than anybody, and they’ve still got most of it left. Their big cap space plans involved signing David West, re-signing Jeff Foster….and that was it. For the most part, the cap space sits untouched, the same team returned, with just West and George Hill for upgrades.

This is perhaps unsurprising. The eminently reputable David Aldridge claimed in the summer that the Pacers lose $15 million annually – it is perhaps therefore unsurprising that they sit $15 million below the salary cap. They’re also doing so with a pretty good team – despite the strange and often incorrect methodology over the recent years, the last few months combined with a couple of good draft picks have seen the Pacers go from the doldrums of the late lottery to being one of the better teams in the Eastern conference. No point spending for the sake of spending.

(Perhaps a lesson there for other moribund teams. You don’t have to completely pull the plug to build something. Something to note for, say, Washington.)

That said, the Pacers really do have to spend some more money. And that is simply because the rules will make them. In addition to a maximum amount of spending (the salary cap), teams also have a minimum level. This is pretty much never relevant – although Sacramento came very close to not meeting it last season – but as a part of the new CBA, the minimum salary cap level was raised from 75% of the salary cap, to 80% for this season, 85% for next season, and 90% thereafter. 85% of the current salary cap of $58,044,000 is $46,435,200; ergo, the Pacers, with their payroll currently at $43,773,036, are $2,662,164 short of it.

In addition to Indiana, a few other teams are below the maximum salary cap. Some, like Golden State ($286,463) and Houston ($777,210) are less than a minimum salary under, but under it nonetheless; furthermore, whilst technically over it because of cap holds, Toronto ($4,301,302) and Cleveland ($6,847,207) could get under it for the right deal. Washington ($1,700,748) and Minnesota ($1,199,661) also have a smattering left, while Sacramento have a very significant $9,429,746 chunk remaining.

As ever, there is scope and logic for a unison between the capspacers and the taxpayers. Trades of spare parts from taxpayers to non-taxpayers happen every year – see moves such as Marquis Daniels to Sacramento, Sasha Vujacic to New Jersey, Steve Francis to Memphis, and many others – and possibilities exist once again.

Having not amnestied him for whatever reason, the Lakers continue to own the determined but redundant Luke Walton, who won’t take a medical retirement and thus burdens the Lakers cap for two more years (and who, with a trade kicker mentioned below, is even harder to deal than it looks). The possibility of Boston being able to shift Jermaine O’Neal, Chris Wilcox, or both, in a bid to save some luxury tax money at the expense of all their frontcourt depth, is vaguely possible albeit an extreme long shot. Meanwhile, Josh Davis has stuck around with the Grizzlies against the odds, providing some front court depth when they had none earlier in the year; however, even without Zach Randolph due to long term injury, Davis is now redundant and taking up cap space. (His non-guaranteed deal can be cut – however, if is traded, thereby removing the already-paid portion of his salary from the Grizzlies’s tax number too, then that’s even better. This is rather easy to do with minimum salary players and happens fairly often.) And Atlanta’s 15 man roster consists of 8 minimum salary contracts, due directly to the less-than-creative contract they gave Joe Johnson. Trading and/or cutting a couple of those dips them just below the luxury tax line, where they had best hope that all the performance bonuses in their incumbent contracts don’t conspire to push them back over it.

The most obvious union, however, is O.J. Mayo and Indiana. The team that owns O.J. Mayo is over the tax. The team that wants him is easily far enough under the cap to absorb him. The two teams have come so close to making this deal that it has been falsely reported as being falsely completed TWICE before (once here, and once here, before it was edited. Smooth.) And Memphis still doesn’t need or use Mayo to any great effect, while Dahntay Jones still needs upgrading.

It writes itself. If you can get $30,000 on O.J. Mayo being a Pacer by March, do so.

|

| ….yeah, no. Just no. |

There follows an updated list of all the trade kickers currently in existence in the NBA.

Since the last list was written, Joel Przybilla, Carmelo Anthony, Chris Kaman and Chris Paul have all been traded, exercising their trade kickers (although in the cases of Anthony and Paul, without actually adding anything to the contract value: see here.) Jeff Foster and Yao Ming’s contracts expired, nullifying theirs; so has Eddy Curry’s, although his was enacted just beforehand upon his trade to Minnesota. Eddie House was cut, Brandon Roy was amnestied, Ron Artest changed his name, Antonio McDyess retired, and, like Curry, Peja Stojakovic was bought out of his deal not long after being traded. New contracts for Tyson Chandler, Vince Carter, DeAndre Jordan and Derrick Rose all have trade kickers in, and the updated list now reads as follows.

– Ray Allen (15%)

– Andrea Bargnani (5%)

– Kobe Bryant (10%)

– Chris Bosh (15%)

– Jose Calderon (10%)

– Vince Carter (15%)

– Tyson Chandler (lesser of 8% or $500,000)

– Tim Duncan (15%)

– Pau Gasol (15%)

– Manu Ginobili (5%)

– Udonis Haslem (15%)

– Eddie House (15%)

– LeBron James (15%)

– Amir Johnson (5%)

– DeAndre Jordan (15%)

– Shawn Marion (15%)

– Mike Miller (15%)

– Jermaine O’Neal (7.5%)

– Quentin Richardson (15%)

– Derrick Rose (15%)

– Josh Smith (15%)

– Anderson Varejao (5%)

– Dwyane Wade (15%)

– Luke Walton (7.5%)

– Metta World Peace (15%)

Either because they’re already earning the maximum, or because they’re highly unlikely to ever be traded, or both, a few of those are perhaps nothing more than arbitrary. It appears, then, that trade kickers aren’t in vogue right now. NBA salary trends tend to oscillate, the NBA being as it is a copycat league, and trade kickers just aren’t as popular as they were five years ago for whatever reason.

However, as spending decreases, contracts are getting shorter. It seems that this year, more than ever, one year contracts were in vogue. This, strangely, gives us a whole new realm of trade kickers to consider, and for people they wouldn’t otherwise be applicable to.

Out-and-out no-trade clauses are incredibly rare in the NBA, as the criteria for being eligible for one are not easy to meet in this day and age. To receive one in a new contract, a player has to have been in the NBA for at least eight seasons, and has played for the team with which he is signing for at least four of them. It is therefore perhaps no great surprise that only two conventional no-trade clauses exist in the league, belonging to Kobe Bryant and Dirk Nowitzki. Not even Tim Duncan has one. (And nor does Paul Pierce, contrary to some reports.)

Yet a mere technicality effectively creates de facto no-trade clauses for a group of players not even nearly meeting those criteria. In a little-known rule made incredibly famous by Devean George, players who sign one year contracts (or multi-year contracts with only one non-option year), who will have early or full Bird rights upon completion of that contract, have the right to veto any trade they may be in, as, if they were to be traded, they would lose their Bird rights and become mere non-qualifying veteran free agents.

Put into practice, if a player earning $4 million on a one year contract will have Bird rights at the end of it, he can re-sign for up to the max when it ends. But if he’s traded and loses his Bird rights, he can re-sign for only 120% of that previous amount, a considerably less impressive $4.8 million. Ergo, they have the right to veto, to preserve their rights and thus their pay day.

At a loss to explain why that rule exists and they would lose their Bird rights in the first place – it probably has something to do with qualifying offers, but this is a mere guess – we can nonetheless document to whom it currently applies.

Atlanta: Jason Collins

Boston: Sasha Pavlovic

Chicago: Brian Scalabrine

Cleveland: Anthony Parker

Dallas: Brian Cardinal

Indiana: Jeff Foster

Memphis: Hamed Haddadi

Miami: Juwan Howard

New Jersey: Kris Humphries

New Orleans: Carl Landry and Marco Belinelli

New York: Jared Jeffries

Orlando: Earl Clark (second year is a player option: can retain Bird rights if invoked prior to trade)

Philadelphia: Tony Battie and Spencer Hawes

Phoenix: Grant Hill

Portland: Greg Oden

Washington: Nick Young and Maurice Evans

With respect to all parties involved, when read against the names of Dirk Nowitzki and Kobe Bryant, that list is quite funny. The Devean George rule has only been used once, and isn’t likely to be used again any time soon, especially since most of the people who could possibly invoke it are veteran minimum salary types to whom the potential loss of Bird rights is meaningless anyway.

Nevertheless, comedy potential exists.

|

| After 12 long and glorious years, Mate Skelin’s NBA career is finally at an end. He’s the one on the right, by the way. |

In one final act of bookkeeping, here is a list of players whose free agent cap holds were renounced this summer by teams looking for cap space.

Golden State – Reggie Williams, Al Thornton and Acie Law

Golden State – Reggie Williams, Al Thornton and Acie Law

Houston – Torraye Braggs, Mark Jackson, Maciej Lampe, Yao Ming, Dikembe Mutombo and Jake Tsakalidis

Houston – Torraye Braggs, Mark Jackson, Maciej Lampe, Yao Ming, Dikembe Mutombo and Jake Tsakalidis

Indiana – Mike Dunleavy Jr, Tyus Edney, T.J. Ford, Jeff Foster, Tim Hardaway, Lari Ketner, Terry Mills, Andre Owens, Brent Scott, Mate Skelin, Rik Smits, Zan Tabak and LaSalle Thompson

Indiana – Mike Dunleavy Jr, Tyus Edney, T.J. Ford, Jeff Foster, Tim Hardaway, Lari Ketner, Terry Mills, Andre Owens, Brent Scott, Mate Skelin, Rik Smits, Zan Tabak and LaSalle Thompson

L.A. Clippers – Ike Diogu, Jamario Moon and Craig Smith.

L.A. Clippers – Ike Diogu, Jamario Moon and Craig Smith.

Milwaukee – Earl Boykins, Primoz Brezec, Damon Jones, Michael Redd and Chris Douglas-Roberts

Milwaukee – Earl Boykins, Primoz Brezec, Damon Jones, Michael Redd and Chris Douglas-Roberts

New Jersey – Mario West, Dan Gadzuric and Sasha Vujacic

New Jersey – Mario West, Dan Gadzuric and Sasha Vujacic

New York – Derrick Brown, Roger Mason, Anthony Carter, Jared Jeffries, Shawne Williams and Shelden Williams

New York – Derrick Brown, Roger Mason, Anthony Carter, Jared Jeffries, Shawne Williams and Shelden Williams

Sacramento – Sam Dalembert, Marquis Daniels, Darnell Jackson and Pooh Jeter

Sacramento – Sam Dalembert, Marquis Daniels, Darnell Jackson and Pooh Jeter

Washington – Larry Owens, Hamady N’Diaye, Othyus Jeffers, Josh Howard, Maurice Evans, Yi Jianlian and Mustafa Shakur

Washington – Larry Owens, Hamady N’Diaye, Othyus Jeffers, Josh Howard, Maurice Evans, Yi Jianlian and Mustafa Shakur

A full list of free agent cap holds can be found here. After Indiana’s long-overdue clearout, that is pretty much it for 90’s relics with Keith Van Horn-like sign-and-trade potential. Only Boston, Dallas, Phoenix, San Antonio and the L.A. Lakers can threaten something like that any more. And with the middle three all looking for cap space some day soon, the list is soon to be further pruned.

Alas.

|

| You can pause any game that Kyle Korver is in, at any moment, and he’s guaranteed to be doing something ridiculous. |

From Creative Financing 2009 part 2 comes this rant:

[…] Of note on this list is the curious case of Channing Frye, the former Blazers and Knicks forward whose transformation from the next Dirk Nowitzki to the next Malik Allen is almost complete. The Suns signed Frye last month to a 2 year, $4,139,200 contract; not coincidentally, that is the same amount as the full value of the Bi-Annual Exception. However, the Suns didn’t actually use their Bi-Annual Exception to sign him. Knowing that they wouldn’t be using the full MLE to sign somebody due to their payroll concerns, the Suns cleverly (and creatively) used an equivalent chunk of their mid level exception instead. As the name would suggest, you get to use the Bi-Annual Exception a maximum of once every two years, so if the Suns used it this year, they wouldn’t get it next year. But if they roll it over, they do. It’s pretty shrewd, when you think about it.

(Teams that should have done this but didn’t include Washington – who used their BAE on Fabricio Oberto, and who won’t use their MLE – and Chicago – who used their BAE on Jannero Pargo and who also won’t use their MLE; however, if their plan for 2010 cap space comes off, it won’t matter.)

From Creative Financing 2010 comes this similar rant:

[…] It turns out that it didn’t matter. As was extremely obvious, Chicago went the cap space route, and after Washington’s fourth annual explosive decompression, so did they. By both going the cap space route, the two teams thereby ensured that the exceptions they might have lost never actually mattered. (Had Washington not finally decided it was the right time to blow it up, they would have been down a BAE this summer for no good reason. It wasn’t a good idea, but they got away with it.)

Only two teams this summer have used their Bi-Annual Exceptions so far. Milwaukee used theirs on ShamSports.com favourite Keyon Dooling, while Detroit used theirs to re-sign Ben Wallace (whose lack of effort during his time with the Bulls has permanently sullied any affection I once had for him). However, while Milwaukee used their BAE because they’d spent their MLE on Drew Gooden, Detroit used their BAE while their MLE sits there untouched. That MLE is probably going to stay untouched all summer, because they’ve certainly shown no inclination to use it thus far, and all the MLE calibre free agents have gone. They could have used it on Wallace so that they could carry over their BAE; they should have used it on Wallace so that they could carry over their BAE. But they didn’t.

As was the case with Washington, this might turn out to be completely insignificant. But what if it isn’t? What was the point of that?

Detroit didn’t have any cap space this year, instead choosing to spend their money re-signing their own team. As such, whereas they could have potentially used the BAE on someone, they couldn’t, because they had unnecessarily used it the year before. It is not a deal breaker or a particularly big deal, but it is a misappropriation of assets for a team with scant few.

It’s also happened again.

Contrary to an ever-more prevalent myth, the Bi-Annual exception was NOT gotten rid of in the new CBA. It still exists; the only significant change to its existence was that taxpaying teams are no longer allowed to use it. Everyone else, however, is.

Few have, though. Indeed, only two teams have cracked the seal on their Bi-Annual exceptions this year, and neither team used all of it. Memphis gave two years and $2 million to Jeremy Pargo, while Toronto one-upped that with two years and $3 million for Gary Forbes.

Both teams also received the non-taxpayer mid-level exception this year of $5 million, and both teams have used part of it. Rather bizarrely, Toronto gave Aaron Gray $2.5 million for one year, where he’s been unlucky enough to miss most of it with a heart problem, while Memphis gave Dante Cunningham $6.27 million over three years for the right to battle it out with Quincy Pondexter and Sam Young for the scant few available backup forward minutes, while also using $550,000 of it to give rookie Josh Selby a three year contract.

You can probably see where this is going. Memphis now have an unusable $900,000 of their Bi-Annual Exception in remainder, while Toronto has an even more unusable $400,000 left over. Yet the two teams sit with a combined $4.95 million in untouched mid-level exception which could easily have accommodated the players on whom they used their Bi-Annual exceptions.

Toronto will likely have cap space next season, rendering this null and void. Memphis, however, won’t. And even if their significant spending in recent months – $245,806,454 in the last 18 months on Marc Gasol, Rudy Gay, Mike Conley and Zach Randolph alone – has greatly handicapped their ability to spend in the future, potentially rendering usage of the BAE impossible anyway, it would still have been more beneficial to retain its usage for next year, however marginally, rather than leaving a chunk of MLE unused that you can’t carry over.

Trivial details, perhaps, but still hard to justify.

|

| Terrible wristband. |

Something never before seen happened on May 30th 2011, as Ricky Rubio signed his rookie contract with the Timberwolves.

If you’re into salaries and the like – which, if you’re reading this post, it is assumed you are – you’ll see an obvious problem there. Minnesota’s season was done with by that times from a games-played standpoint, yet seasons officially change from one to the next on July 1st every year (which is why that was the date that the lockout starts, and that the moratorium normally starts). Ergo it appeared that Rubio had signed for the final month of the season, and the final month of the season only, even though there was no game action in it.

But he didn’t.

In a move I have never seen before – and which I didn’t even know was possible – Rubio seems to have signed his contract in advance – that is to say, Rubio signed a four year contract, yet it did not begin until after the NBA lockout. Normally, contracts signed for part-seasons count as full seasons, even if they leave it as late as signing on the last day of the regular season. In Rubio’s case, however, it was adjudged that the end of the 2010/11 season didn’t count – therefore, his four year contract began when this season did, and will run until 2015.

Furthermore, the previous CBA contained rookie scale figures for the 2011/12, even though there was an option to terminate the agreement before that season began (which is what inevitably happened). So when Rubio signed his deal in May 2011, under the old CBA, he signed for the scale amount for the 2011/12 5th pick under the OLD CBA’s figures, rather than the new ones. This is noteworthy for one reason: the 2011/12 figures under the old CBA were slightly higher.

Thus, even though those figures are otherwise not in use, they apply to Rubio. And instead of earning the $15,239,922 over four years that he would have done had he signed under the new CBA’s scale amounts, Ricky will instead get $16,294,046 over that time span, an increase of $1,054,124. Score a point for his agent.

I have no idea what provision in the CBA, what piece of language from whence it came, where said Rubio mechanism can be found. But for the purposes of us as outsiders, that matters not. It matters only to know what Rubio is signed for, and for how long.

And even that doesn’t really matter either.

But it is different.

[Something similar has happened for Patrick Beverley. Last training camp, Beverley signed a fully guaranteed two year minimum salary contract with a drunken Miami Heat front office that was so happy with their 2010 haul that they were throwing money away, even giving $250,000 to Kenny Hasbrouck. Beverley did not make the team and was cut, but nevertheless still stood to make his two years of minimum salary money, since it was guaranteed. The 2005 CBA contained minimum salary values for a potential 2011/12 season, in the same way as it had rookie scale amounts for that year also drawn up. In those minimum salary values, second year players stood to make $788,872. However, when the new CBA was drawn up, it was agreed that all minimum salary values were frozen for two years, and that therefore the 2010/11 amounts are to be used both this season and next. That means that the two year minimum is the same as it was before, $762,195. Beverley, however, will uniquely get the $788,872 that he was promised. A quirk of the system, perhaps, but a welcome $26,677 for Pat. Score one for his agent too.]

|

| I don’t understand the panning of Hasheem Thabeet. He averaged a double double only three years ago. |

In the run-up to the lockout, many third and fourth year contract options were exercised by teams on their incumbent rookie scale contracts, a process which normally doesn’t happen until October. Indeed, almost all of them were, to the point that it’s easier to list the ones that weren’t.

– Charlotte: Gerald Henderson

– Houston: Jonny Flynn, Hasheem Thabeet, Jordan Hill and Terrence Williams

– Memphis (now New Orleans): Xavier Henry and Greivis Vasquez

– New Jersey: Damion James

– New Orleans (now Memphis): Quincy Pondexter

– New York: Toney Douglas

– Orlando: Daniel Orton

– Philadelphia: Craig Brackins

– San Antonio: James Anderson

Due to the lockout, the usual October 31st deadline for these options was put back to January 25th. So there’s still time.

[NB: Despite no customary press release saying so, Detroit did in fact exercise their options for Greg Monroe and Austin Daye back in June.]

Furthermore, the largely arbitrary nature of rookie scale contracts can cause one other conflict. As we found out last year – described AT LENGTH here – having performance incentives in rookie scale contracts is a controversial topic. It is, however, normally for trivial matters, such as participation in summer leagues, summer conditioning programs, and the like. Rare is the day that actual on-court performance bonuses are included in rookie scale contracts. However, as that study found out, it does happen.

(A very thorough breakdown of the situation can be found by reading that post, as well as the one its first sentence links to.)

What we also found in there was that only on a scant few occasions has a rookie been given less than the maximum 120% of the rookie salary scale. Indeed, as best as can be ascertained, it has happened five times prior to this season: Donte Greene, Sergio Rodriguez, James Anderson, George Hill and Ian Mahinmi.

Add two more to that list.

Predictably, one of them is a Spur. While Kawhi Leonard got his full 120%, Cory Joseph didn’t. He can earn it by meeting his incentives – and, as best as can be ascertained, there are no on-court performance bonuses included in his deal – yet as of right now, he’s at only 100%. Considering that the Spurs are responsible for three of the five previous non-120%ers, and that there was absolutely no chance that Joseph was going in the first round were it not for San Antonio, this is not surprising. They had all the leverage.

The other non-120%er, though, is from a more surprising source. Despite his blistering start to the season, with averages of 15.1 points and 4.4 rebounds at the time of writing, MarShon Brooks is doing so for only 115% of his possible rookie scale amount. He stands to gain 120% in all future years – however, this season, he is earning only $1,063,865 of the $1,110,120 that he could be. The reason why is not apparent, but also perhaps not important.

Of course, saving $46,255 on MarShon Brooks’s contract is less impressive when you then re-invest it all on three weeks of Dennis Horner. Or when you decided that, despite being a mere shell of his former self, Mehmet Okur was totally worth $10,890,000 for one season of backup-calibre play.

But I digress. For whatever reason, and via whatever methodology, the Nets creatively found some extra cap space.

(Incidentally, how favourable has time been to Memphis’s infamous attempt to offer less to Xavier Henry and Greivis Vasquez? Somewhat. Amidst other criteria, the main stipulation that the pair had to meet was averaging 15 mpg in a minimum of 70 games played. Vasquez came close, playing in the 70 games yet averaging only 12.3mpg, while Henry wasn’t even in the same ballpark, averaging 13.9mpg but in only 38 games. Furthermore, neither is even with the team any more. So the Grizzlies’s intent to save money by not giving it to those who did not deserve it with their play was not baseless. But then again, it never was. That doesn’t change that the fact that, however justifiable the conduct on a wider scale, it was the wrong team at the wrong time. You’ve got to pick your battles.)

|

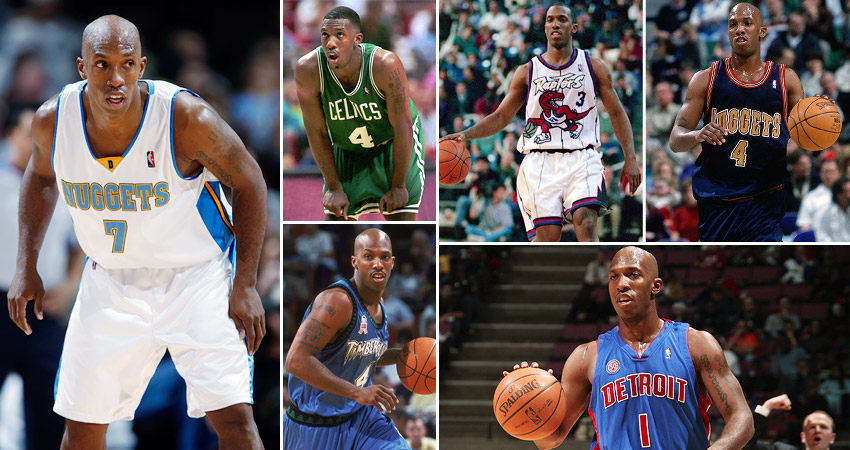

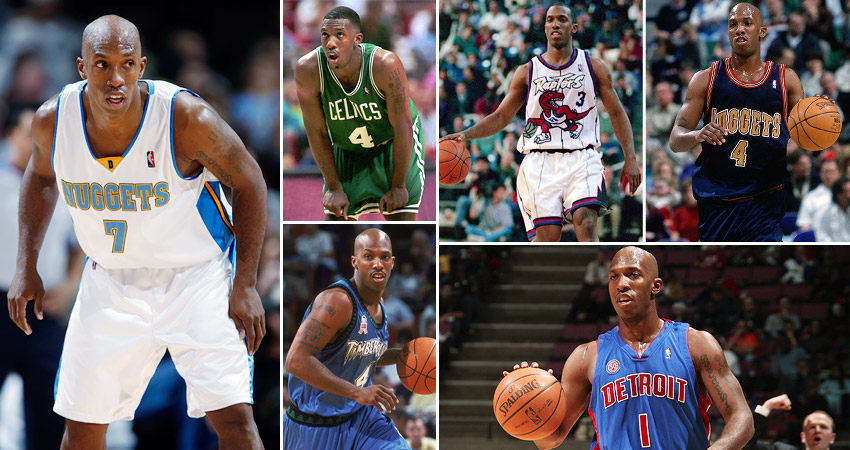

| Add them all up, and you get……a number that isn’t 32. |

And finally.

The new look amnesty clause claimed seven victims out of a possible thirty this offseason; Baron Davis, James Posey, Chauncey Billups, Charlie Bell, Brandon Roy, Travis Outlaw and Gilbert Arenas.

Four of them have landed elsewhere. The Knicks signed Davis for the minimum, and not for the non-taxpayer MLE as was initially widely reported. Bell meanwhile returned to Italy, the home of his best years, where he’s shot 6-28 in three games. But the other two were the first and thus far only two recipients of the new amnesty waive claim procedure.

The amnesty claims procedure allows those under the cap to enter into an MLB-like blind bidding procedure for their services. Several wondered whether this would lead to MLB-like incredibly specific bid amounts.

With only two bids in, it already looks like we will. One of them is normal enough, if rather regretful – for some reason, Sacramento bid an even $12 million for Outlaw, bidding up themselves and getting lumbered with an average backup on a guaranteed four year contract at a position where they were already set for averageness. A confusing move salvaged only by its novelty.

Billups, however, was the more beautiful novelty. In bidding for his services, the Clippers served up a bid for the very specific amount of $2,000,032. Not only is this amount an undeniable bargain when compared to the $4.25 million Randy Foye is getting to back him up – or the $3 million Outlaw is getting to shoot 24% from the field – it’s also beautifully unique. Is the additional $32 supposed to be representative of a number special to Billups? If so, why? If not, and it’s a random number they just chose, why 32? Why not $25? Why not $825? And was any team out there stymied by it, unlucky enough to serve up a losing bid of exactly $2 million?

That, there, is creative financing in action. After all, we were never going to be completely denied it.