Creative Financing in the NBA, 2010

August 12th, 2010

Last year, I wrote a couple of posts under the heading of “Creative Financing in the NBA.” Inspired by seeing a series of quirky salary techniques that I had not previously seen in my three long and sexless years of compiling NBA salary information, I was inspired to steal Magic GM Otis Smith’s favoured phrase without permission, and use it to describe some of the financial anomalies that the offseason transactions had puked over our spreadsheets. The posts were reasonably successful, drawing in both the 25th and 26th regular viewers to the site; more than anything, however, they were a pleasure to write.

Last year, I wrote a couple of posts under the heading of “Creative Financing in the NBA.” Inspired by seeing a series of quirky salary techniques that I had not previously seen in my three long and sexless years of compiling NBA salary information, I was inspired to steal Magic GM Otis Smith’s favoured phrase without permission, and use it to describe some of the financial anomalies that the offseason transactions had puked over our spreadsheets. The posts were reasonably successful, drawing in both the 25th and 26th regular viewers to the site; more than anything, however, they were a pleasure to write.

Therefore, there follows another post for salary anomalies and trivia from the 2010 NBA offseason, a breakdown of all quirky payroll-related idiosyncrasies and manipulation that took place in front of our very eyes, even if we didn’t really notice it at the time. Note: this will not interest you, unless you are really big on pedantry.

(Mind you, that could be said about this entire site.)

– One of the first signings announced in this free agency period was that of Amir Johnson, who last year backed up Chris Bosh in Toronto. He played well, being possibly Toronto’s best defender and averaging 6/5 in 17.7 minutes per game with a PER of 16.7. The Raptors re-signed Johnson to a deal worth $30 million in base compensation (not $34 million as was widely reported), with incentives in the deal to potentially boost its value that are currently listed as “unlikely.”

Amir’s contract before incentives will pay him $5,000,000 next year, rising by $500,000 annually to a total of $7 million in the fifth and final year. However, that $7 million salary in the final year is only $5 million guaranteed; if Toronto (or whoever owns him at that time) waives him, that’s all they’ll pay him. He’ll be off the team, of course, yet the team will save $2 million.

[Note: for the purposes of the upcoming blurb, team options in rookie scale contracts are ignored, since they are mandated.]

Unguaranteed or partially guaranteed final seasons are becoming quite the trend in the NBA, and they are quickly replacing team options. In fact, there are only 11 team options in the entire league, belonging to Chase Budinger, Jermaine Taylor, Andrew Bynum, Sam Young, Andres Nocioni, Hakim Warrick, Goran Dragic, Pooh Jeter, Francisco Garcia, Solomon Alabi and C.J. Miles. In contrast, there are so many partially or fully unguaranteed contracts in future years that I can’t be bothered to go through and list them all. And considering the length of this post, and all the things I could be bothered to do, that should signify something.

(For all salary details, visit the salaries pages. And for more information about specific unguaranteed deals, read below.)

In Amir Johnson’s case, the unguaranteed portion of the deal means very little. His contract currently costs $6 million annually; all that waiving him will do will raise that per annum cost to $7 million. As unguaranteed contracts go, it’s almost as useless as Eduardo Najera’s current one, which had all but $500,000 guaranteed in his final two savings, for no obvious reason. (It is now fully guaranteed.) Nevertheless, the trend for including a partially guaranteed final season/s for non-star players continues.

There are very few instances in which contracts must be guaranteed. In fact, there are only two; the first year of a signed-and-traded contract, and the first two years of a rookie scale contract (which must be guaranteed for a minimum of 80% of the scale amount). Nothing else has to be guaranteed, but it is self-evident that almost all are. Would you accept an unguaranteed contract as a player? Not without incentive to do so, no. It is self evident why so many contracts are fully guaranteed. Yet the unguaranteed contract fad has its basis in logic.

In a lot of cases, unguaranteed contracts function much like team options do. However, there are some significant advantages to doing it in this way, which is why it happens. The differences:

1) Team options have to be decided upon by the final day of the previous season. Seasons change over on July 1st, and thus team options must be decided upon by June 30th. This is not the case with unguaranteed contracts, which either have guarantee dates that can be negotiated to different dates, or which have no guarantee date at all. A lot of unguaranteed contracts have some guaranteed money, becoming fully guaranteed upon a certain date, or no guaranteed money at all becoming slowly guaranteed upon several dates; for players earning the minimum salary is often the latter, which bigger contracts are usually the former. Common dates include July 15th (two weeks after free agency starts, giving teams times to analyse the situation), August 1st (same sort of thing) and August 15th (for the very tardy); however, in practice, anything goes. In this way, these contracts serve as delayed team options.

Sometimes, such as in the case of Ian Mahinmi’s second season, the contract is fully unguaranteed if not waived on or before June 30th, thereafter becoming fully guaranteed. Contracts with guarantee dates such as those are basically exactly the same as team options; however, the reason they are not done with team options is because of the reasons below.

2) Salaries for option years in contracts cannot be for a lesser salary than the salary of the previous season. But no such stipulation applies to unguaranteed years. One such example of this is with the recently expired contracts of Steve Blake and Travis Outlaw. Blake’s contract paid $4.25 million in its first two seasons, dropping to $4 million in the final one; Outlaw’s contract was $4 million for two seasons and then $3.6 mil for the third. By making the final seasons for the duo unguaranteed, even though they had June 30th guarantee dates that made them basically team options, the Blazers were able to use the lower salary trick.

3) Players can be traded from the minute a team’s season ends, up until the start of the moratorium (so for lottery teams, that’s mid April until the end of June.) This is how draft night trades are allowed to happen. However, players can only be traded if they’re not going to be free agents that summer, or if they have no options that would allow them to become so. If they have an option, player or team, then that option must be exercised concurrent with the trade, and thus the player will not be a free agent. Teams can bypass this by making the final year an unguaranteed season, rather than an option year. This is how Erick Dampier was traded. It is also how Ryan Gomes was traded before free agency started.

Lords Of The Unguaranteed this offseason were Chicago. The contracts they gave to all three of C.J. Watson, Ronnie Brewer and Kyle Korver all have unguaranteed third seasons. Watson’s and Brewer’s are evidential of the aforementioned delayed-team-option thing, fully unguaranteed contracts that become fully guaranteed if not waived on or before July 10th. Korver’s is different; he has $500,000 in guaranteed compensation, yet has no contract guarantee date (save for the league-wide guarantee date of January 10th), and will thus be an incredibly useful trade chip that summer because of reason 3 above. It is largely for this reason that unguaranteed contracts are so en vogue right now.

(Incidentally, the wonky up-and-downy contracts the Bulls have handed out are done so entirely deliberately. It is not a coincidence that Carlos Boozer’s salary takes a significant upstroke only after that of Luol Deng has expired; similarly, it is not a coincidence that these three unguaranteed contracts all come in the summer that Derrick Rose will need paying. It is not a coincidence that Brewer and Watson’s contracts goes down over their lifespan, nor that J.J. Redick’s would have done, nor that Korver’s flatlines, nor that Boozer’s hits its lowest point at the time Joakim Noah will need a new contract. Once the max-slot guys all agreed to sign with Miami, Chicago’s priority became obtaining good quality role players at competitive prices while maintaining roster flexibility. They have done it well, even if they still need another shooter.)

The downside to doing it this way is that players have to be waived for the savings to take effect, which means they get renounced in the process. In contrast, if a team declines a player’s team option, they would still have Bird rights on that player in order to re-sign them, and they could also still extend a qualifying offer (if applicable). By being waived as an unguaranteed contracts instead, those benefits are lost. But that minor inconvenience is more than offset by the benefits to such a team-friendly mechanism, which is why its usage is becoming increasingly prevalent in the NBA.

– There follows a Youtube video of a song that signifies everything that is wrong with hip hop music today.

Celtics swingman Marquis Daniels appears on the above track, under his rapping soubriquet (is that the street term?) of “Q6.” Marquis contributes the first verse on this frankly seminal smash, bringing us an intricate narrative of a time he went out for a quick evening beverage in his favourite evening garments, and found himself involved in all kinds of hilarious capers.

(No, really. It really is him doing the first verse. As proof of sorts, here is Marquis appearing as Q6 in a studio, in the midst of recording another song, with a self-confident man who laments society’s portrayal of him as being overly gangster, which he considers to be an unfair misrepresentation of his personal doctrine. He is wearing more than one chain.)

In addition to making musical history, Daniels also had some basketball business to take care of this summer, and did so when he re-signed with the Eastern Conference champion Boston Celtics a couple of weeks ago. Daniels signed a one year deal worth exactly $2,388,000, the maximum he was able to receive under the non-Bird exception, precisely 120% of his previous salary of $1,990,000.

Daniels had signed that one year, $1.99 million deal last summer; it was seemingly the best contract he could get, even though he had put up his best season in 2008/09 since his rookie year. He then proceeded to put up career lows across the board for Boston, averaging only 5.6 points, 1.9 rebounds and 1.3 assists per game, scoring only 11 points per 36 minutes, playing only 51 games due to injuries, rocking a PER of only 9.6, and still being unable to shoot threes. However, he played slightly better than those raw numbers indicated, shooting 50% from the field, playing decent defence at the small forward position (to which he is not really suited), and making a valiant effort at playing as an emergency point guard (at which he is equally unsuited). He was also pretty good in the playoffs, and so although he had played his worst season to date, Boston saw fit to re-sign him.

Of course, they would not have had to do so had they signed him to a two year deal in the first place. Five players signed full BAE contracts for only one season last year, and Daniels was one of them; by having only spent one year with the team, Boston had only non-Bird rights on him. That limited them in what they could offer, only able to offer a contract starting at 120% of Daniels’s previous salary, for a maximum of five years. However, this $2,388,000 figure represents a larger amount that Daniels would have received had he signed a two year deal initially ($2,149,200). And all he did in between was put up his worst ever season.

On the surface, that looks suspicious. Why would a player who played as well as Daniels did in 2008/09 (13.6ppg, 4.6 rpg, 2.1apg) take a contract so far below his market value, just to then play worse and yet get a maximum raise anyway? On the surface, it looks premeditated, Joe Smith-esque, a pre-conceived sequence of events designed to get Daniels more money in the future in exchange for taking less now. (All $100,000 of it.)

However, I’m not saying it was cap circumvention. It wasn’t; it just looks weird. Both contracts were all that Boston could give him, and if Marquis was willing (or only able) to take those two separate deals rather than whatever offers were extended elsewhere, then that’s his perogative. Boston had spent their whole MLE already this year on Jermaine O’Neal, and had done so last year on Rasheed Wallace; without Bird rights, an MLE, or any other mechanism for signing him, the Celtics HAD to use their BAE and non-Bird exceptions on Daniels. There was no other way. And Daniels essentially HAD to take one year deals, knowing that he was being underpaid for his talents (use of past tense deliberate), and needing to test free agency again at the earliest possible opportunity. Neither party was diddling the system. There was no circumvention.

But you just don’t seem that normally, and so that’s why it was interesting. Especially since he can’t now be traded. More on that later.

(Bonus Marquis Daniels trivia: Daniels has a tattoo on his arm in Chinese characters which, he thought, represents his initials. It actually translates, however, as “healthy woman roof.” Similarly, Shawn Marion wanted one that said “The Matrix” in Chinese, but actually came away with “demon bird moth balls.” It doesn’t get much more fail than that.)

|

| Griz lies. |

– In last year’s first creative financing post, I wrote this:

It’s never really mentioned, because it’s never really important, but most rookie scale contracts contain performance incentives. So widespread is it, in fact, that every first rounder signed this season has them except for Tyreke Evans, Jonny Flynn, Austin Daye, Eric Maynor, Darren Collison and Wayne Ellington. (Yes, even Blake Griffin has them.)

Twelve months later, this factoid became far more important than we knew, purely because of the Xavier Henry saga.

Of the 30 first-round draft picks in this past draft, 28 have signed. Rookie first rounders often sign without fanfare, and sometimes without as much as a press release, since there’s not really anything to announce. With only the rarest of exceptions, first rounders were drafted to be signed straight away, so it doesn’t really need breaking when, say, John Wall signed his rookie contract. (Google “Washington signs John Wall.” This is the only website you will find.) Sometimes it goes unannounced before it is even announced; Wizards draftee Kevin Seraphin signed his rookie deal about a week before it was announced, in a scoop I wish I’d tried a bit harder to publicise. But regardless of how quietly these signings happen, they happen. And with Cavaliers draft pick Christian Eyenga (30th overall pick in 2009) also signing a rookie scale contract, 29 rookie contracts in total were signed this summer.

The only two players from the 2010 draft that have not signed theirs are the two picks that the Grizzlies didn’t sell; Xavier Henry (#12) and Greivis Vasquez (#26).

Nothing is said about why Vasquez hasn’t signed, although the fact that he just had his ankle scoped may well factor. Henry, however, is the subject of a broo-haha. A rum-do. A fracas. A rumpus. Henry – or perhaps more specifically, Henry’s agent Arn Tellem – are offended at the Grizzlies suggestion that Henry sign a rookie contract that includes performance-related incentives. He sat out of summer league play due to the drama, ensuring that the beef has been taken public, and the Grizzlies have thus been made to look like a cheap, reprehensible franchise.

However, as we learnt in the above quote from last year’s post, the inclusion of said incentives is standard practice. So what’s the problem?

Of the aforementioned 29 players signed so far, all but Wesley Johnson, DeMarcus Cousins, Greg Monroe, Gordon Hayward, Avery Bradley, Craig Brackins, Quincy Pondexter and Lazar Hayward have performance incentives in their contracts. This means that the top three picks all have them, as do most of the ones below them. So when I say it is standard practice to have performance incentives in rookie scale contracts, I am not just yanking your crank. It really is.

After negotiations for player’s first NBA contracts started getting insanely insane – punctuated by Glenn Robinson’s 10 year, $84 million deal after being drafted 1st overall in 1994 – the NBA brought in the rookie scale. First rounders are now extremely limited in the contracts they can sign; in a more rigidified version of MLB’s slot system, the amount of years and money that first rounders can sign for is all predetermined. Players can sign for 80% of that amount, 120% of that amount, or anywhere in between……but for nothing more and for nothing less.

It is customary for players to sign for 120% of the scale. In all the years I have done this [not including this year; more on that later], I only known of four players that haven’t; Sergio Rodriguez (signed for 100%), George Hill (signed for 120% for the first two years, then 80% for the final two), Donte Greene (signed an incentive laden contract that he hasn’t yet got up to 120%) and Ian Mahinmi (all over the show). More specifically, as mentioned above, it is customary for players to sign for a guaranteed 100% of the scale, whilst earning the last 20% in incentives.

There is absolutely no rule about that, other than to declare 120% as being the maximum allowable amount. There is no stipulation that a player must get that much; they just always do so due to precedent. As I said, only four players have ever signed for less than the maximum 120%, even if several hundred have been eligible to do so. It is evident, therefore, that the precedent is strong, and that the protocol is set. Regardless of whether incentives are used, 120% is the standard operating procedure.

But what do those incentives entail?

In last year’s second creative financing post, I included a brief breakdown of the incentives Ty Lawson had in his contract with the Denver Nuggets.

To earn the full 120% of his rookie contract that he signed for, Lawson has got to make five promotional appearances for the Nuggets, play in summer league, play in another two week summer skills and conditioning program, and play 900 minutes next season.

Incentives in rookie contracts usually come in two forms; promotional incentives and performance incentives. Promotional incentives – such as that which appears in Lawson’s contract above – are irrelevant to a player’s salary cap number. If they make the appearances, they get the money, and if they don’t, then they don’t. Whichever it is, it doesn’t change the cap number. That is not however the case with performance incentives.

Lawson’s incentives are pretty standard practice, although his minutes per season requirement is pretty harsh. (He made it comfortably, but many others wouldn’t.) It is incredibly normal for rookies to sign rookie scale contracts featuring incentives requiring both summer league participation and appearances at summertime conditioning programs. Those are almost always included; any additional performance bonuses on top of that, such as Lawson’s minutes played requirement, are both rarer and more varied.

Quite what incentives Memphis are demanding that Henry and Tellem accept is not clear. It seems inevitable that Memphis IS breaking protocol, when you consider the following factors;

1) Arn Tellem has signed players to rookie contracts that start at 100% and use incentives to get to 120% in previous years; he did this only last season with Gerald Henderson, and in 2008 with both Danilo Gallinari and Anthony Randolph. He knows the rules and has played by them before.

2) Memphis signed Hasheem Thabeet and DeMarre Carroll to the standard contract of 100% + 20% in likely performance incentives, as recently as last year. They know the protocol, too, and historically have always played by it.

(There exists the third option; that Tellem and Henry are overplaying their hand to deliberately force a trade away from Memphis. I do not buy that one, however, and will thus give it no further consideration.)

It therefore seems like an inevitable and accurate conclusion that the game got switched, and that Memphis is making a greater-than-usual demand on Henry’s incentives. Maybe they’re asking he plays 1,200 minutes, or averages 26 points per game, or shoots greater than 68% from the field, or some combination thereof, in order to get the full 120%. We the public don’t know that.

However, while what Memphis is doing might be different from the norm, it is not necessarily wrong. In this current economic climate, NBA franchises are imploring to us that they’re losing too much money and need to redraft the entire collective bargaining agreement, while also continuing to throw the gross national product of Micronesia at a whole host of players that don’t deserve it. (Memphis are as guilty of this as anyone, with their wildly excessive max contract to Rudy Gay.) While complaining with one arse that their expenditure outweighs their income, owners are using their second arse to wildly overpay the underdeserving, greatly increasing that expenditure level while under pressure from nothing but their own aspirations. We’re looking at an impending lockout a mere 11 months after learning that Johan Petro got an 8 figure contract. Joe Johnson got the fifth highest contract in the history of the sport. Rudy Gay got the max. Chewbacca lives on Endor. It does not make sense.

Rookie scale contracts are not the biggest reason for this double-standard, yet they are a part of it. They represent one more way in which owners are giving players more than they have to. As the examination above has shown, there exists a strong precedent for doing so, yet there is not a rule. If Memphis are looking to buck a trend and start a protocol of their own, whereby a rookie earns their money, then I can’t really fault them, even in light of the Gay hypocrisy. If they are offering Henry (and Vasquez) 100% of the scale guaranteed, with the maximum amount available in incentives that are slightly harder to reach than normal, then what, really, is wrong with that?

Not a lot. But this is Memphis, so the world assumes the worst.

(A fifth player joined the less-than-120% club this year; Spurs draft pick and England frontline seamer James Anderson. After about a month of negotiations, San Antonio eventually signed Anderson to a contract that pays a maximum of 120% of the scale in the first year, but only 115% in the second year, and 117% in the third (fourth year salaries are calculated as a percentage of the third), all years of which contained more significant performance incentives than usual. This is the kind of thing Memphis are accused of being doing, if not an even more extreme example. Furthermore, this now means that three of the five players to have received less than the full 120% have been Spurs picks. They’ve actually gone through with the deed Memphis stand accused of trying, and they’ve done so on an annual basis. In the cases of Mahinmi and Hill, San Antonio could invoke the “no one else was drafting you that high, so live with it” excuse. Not so with Anderson. San Antonio have better leverage, given their strength as a franchise and the fact they aren’t doing it with lottery picks, yet it is the same practice.)

This is not a sweeping, all-encompassing defence of Memphis. I personally believe they handled their draft very badly. Henry was the right pick, and Vasquez was OK, but a team ostensibly designed (if not mandated) to build through the draft decided to sell a first rounder (Dominique Jones, #25) for $3 million, which seems like a hypocrisy and a grave misallocation of assets. (It’s an even graver error when that $3 million is instantly invested in Tony Allen, who will earn that much just to play 1,500 minutes at backup shooting guard next year. In a role Dominique Jones could easily have played. For less money. And for four years.) It also further defies belief why the same draft-built team, with no realistic short term goals, decided to trade a first rounder for a player (Ronnie Brewer) whom they then refused to extend a qualifying offer to. Those two moves ensured the loss of two first-round picks in ways that not even Ted Stepien could replicate; to claim that this Henry diatribe of mine is nothing but the continuation of an endless campaign to defend every move the Memphis Grizzlies make would be unfair.

The Henry saga, however, is not one such mistake. Unless Memphis really are trying to diddle Henry in an unfair manner, or are setting the bar in his incentives unrealistically high, then what they are doing here is not a mistake. While the player has only the power of the agent (which, in the case of Arn Tellem, is significant), the team holds all the leverage. Henry can either accept the offer, or not play in the NBA. The offer Memphis wants him to accept will see him attain a competitive pay rate with his peers, whilst obtaining the maximum salary that they are able to pay him, as long as he proves to be more useful than a paper condom.

The Spurs use this creative manipulation of the rookie salary scale protocol all the time. In fact, they’re worse for it; there were no incentives that George Hill could meet in order to get his 120%. He was getting only 80% regardless (and since 80% of the third year of George Hill’s rookie contract actually worked out to less than the minimum salary, he had to be bumped up to that by the league instead.) The Spurs knew what they were doing here, just as they did when they did it to Anderson last week. The only people who didn’t know were the fans, and that’s because no one sought to tell them.

When San Antonio do it, it’s “shrewd.” When Memphis do it, it is “cheap,” and representative of a moribund franchise that needs contracting. This is the prevailing attitude born out of a desire to disparage the Grizzlies at every juncture, symptomatic of a wider problem of favouritism for certain executives by certain media. For example; Daryl Morey is a vastly superior general manager to David Kahn, but why did the very similar mistake signings of Ryan Hollins and David Andersen, and their subsequent correcting trades, get different levels of press? Because Morey is good and Kahn is bad, thus Morey’s mistakes are all minor while Kahn’s are all major. There’s an element of truth to that logic, yet it is all overblown.

The same is true of the Spurs’ and Grizzlies’ handling of this year’s first-round draft picks. If it’s wrong when Memphis do it, it’s wrong when San Antonio do it. And since it’s not wrong when San Antonio do it, it’s not wrong when Memphis do it either. It’s not going to be wrong when any team does it. Perhaps more of them should.

I appreciate this post is quite hard to read when obstructed by the massive chip on my shoulder.

– One final note about rookie scale contracts; in last year’s post, I also wrote this:

[T]his season, the Indiana Pacers found a new way to make things interesting. When signing Tyler Hansbrough, they gave him the customary 120%, but with an interesting caveat; all four seasons of the contract are only 80% guaranteed. (Note: that’s all that rookie scale contracts have to be guaranteed.) The purpose of this isn’t entirely obvious; if Hansbrough really sucks or dies or something, the option years won’t be exercised anyway, so having a partial guarantee on them doesn’t make much of a difference. But it’s interesting because it’s creative. And, dammit, that’s what we’re after.

This is no longer the case. Hansbrough’s contract is now like the rest of them; 100% guaranteed, with the final 20% available in likely incentives.

Whether the terms of the contract were changed, or whether they were just incorrectly listed in the first place, is not immediately clear. Either way, scrub this anomaly from your mind.

– In last year’s second creative financing post, I wrote this:

As a part of the new scheme of turning this website’s salary information from a static exhibit into a working reconstruction of life in First World War France, there now exists a page that lists all remaining salary cap exceptions for every NBA team. Of note on this list is the curious case of Channing Frye, the former Blazers and Knicks forward whose transformation from the next Dirk Nowitzki to the next Malik Allen is almost complete. The Suns signed Frye last month to a 2 year, $4,139,200 contract; not coincidentally, that is the same amount as the full value of the Bi-Annual Exception. However, the Suns didn’t actually use their Bi-Annual Exception to sign him. Knowing that they wouldn’t be using the full MLE to sign somebody due to their payroll concerns, the Suns cleverly (and creatively) used an equivalent chunk of their mid level exception instead. As the name would suggest, you get to use the Bi-Annual Exception a maximum of once every two years, so if the Suns used it this year, they wouldn’t get it next year. But if they roll it over, they do. It’s pretty shrewd, when you think about it.

(Teams that should have done this but didn’t include Washington – who used their BAE on Fabricio Oberto, and who won’t use their MLE – and Chicago – who used their BAE on Jannero Pargo and who also won’t use their MLE; however, if their plan for 2010 cap space comes off, it won’t matter.)

It turns out that it didn’t matter. As was extremely obvious, Chicago went the cap space route, and after Washington’s fourth annual explosive decompression, so did they. By both going the cap space route, the two teams thereby ensured that the exceptions they might have lost never actually mattered. (Had Washington not finally decided it was the right time to blow it up, they would have been down a BAE this summer for no good reason. It wasn’t a good idea, but they got away with it.)

Only two teams this summer have used their Bi-Annual Exceptions so far. Milwaukee used theirs on ShamSports.com favourite Keyon Dooling, while Detroit used theirs to re-sign Ben Wallace (whose lack of effort during his time with the Bulls has permanently sullied any affection I once had for him). However, while Milwaukee used their BAE because they’d spent their MLE on Drew Gooden, Detroit used their BAE while their MLE sits there untouched. That MLE is probably going to stay untouched all summer, because they’ve certainly shown no inclination to use it thus far, and all the MLE calibre free agents have gone. They could have used it on Wallace so that they could carry over their BAE; they should have used it on Wallace so that they could carry over their BAE. But they didn’t.

As was the case with Washington, this might turn out to be completely insignificant. But what if it isn’t? What was the point of that?

– As an addendum to the above, Phoenix used their MLE this summer to re-sign Frye to a 5 year, $30 million contract, after Frye opted out of the second year of his BAE-equivalent contract outlined above. This means that Phoenix have used some of their MLE on the same player for two consecutive seasons.

That has to be a first, surely.

|

| Brian Butch at something less than his best |

– In last year’s post, I also wrote this:

[T]he Magic signed [Mike] Wilks to an unguaranteed contract for training camp, somewhat expecting him to make the team but absolving themselves of all liability if something better came along. However, during a preseason game on October 16th, Wilks tore his knee up. Badly. He completely tore his ACL, slightly tore his MCL, and badly sprained his meniscus, knocking him out for the season. Because he was under contract to the Magic at the time, the Magic were now liable for his salary until he returned to full health.(That’s the rule. Same as any job, really.) And this meant his contract became guaranteed.

This is why the Magic kept Wilks on the roster for half a season, despite him not playing any games; they were stuck with paying him anyway, so they might as well keep him around. They only shifted him from the roster when they were able to include him as salary filler in the Alston trade, sending him to the Grizzies, with whom he stayed on the roster until the end of the year. That was Mike Wilks’s year in a nutshell – two teams, 7 months, 1 injury, 0 minutes played, over a million dollars earned. Could have been worse, I suppose.

The same thing happened to the Heat. Always willing to play the training camp game, Miami obliged us once again last year by bringing in the full compliment of 20, even when most of the extra signings (Omar Barlett, Tre Kelley, Eddie Basden, Matt Walsh, David Padgett) had no real chance of making the team. Along with Padgett, they signed former Davidson point guard Jason Richards right after summer league, to a contract that had only $50,000 guaranteed. However, Richards too blew out his knee, and so the Heat were liable for his salary until the day he recovered. And that saw them have to pay him for the full season.

The worst part about it all was that Richards’s now-guaranteed salary meant that the Heat were now going to be taxpayers, when previously they’d budgeted to be just under it. As a result, they had to salary dump Shaun Livingston, now the Thunder’s premier backup. Bad times.

It’s happened again. In his second summer league game, Nuggets big man Brian Butch took a bad fall during the third quarter, dislocated his knee cap, and ruptured his left patella tendon. It’s a serious injury that puts Butch’s career on hold just as it was hitting its highest point; the positive from this extremely painful negative is that he was under contract at the time.

There’s been a trend lately for signing players contracts for the final few days of the regular season, that run through the following season with little or no guaranteed salary. Players to have done it last year include Oliver Lafayette and Tony Gaffney (Boston), Rob Kurz and Chris Richard (Chicago), Coby Karl (Denver), Reggie Williams (Golden State), Mike Harris and Alexander Johnson (Houston), Greg Stiemsma (Minnesota), Dwayne Jones (Phoenix), Alonzo Gee, Garrett Temple and Curtis Jerrells (San Antonio), Joey Dorsey (Toronto) and Othyus Jeffers (Utah). Any of them could have gone down with a serious injury, and only one of them did. That was Butch. But fortunately for Brian – if that’s not a contradiction in terms – he had a contract as well.

Unless there’s something I’m not aware of – which is entirely possible as an outsider – Denver now must pay Butch’s salary until he is healthy again. Significantly, Butch’s contract as it was written was fully unguaranteed until August 15th, at which point it became fully guaranteed. Butch is likely to be out for the year, as the injury is a severe one, so a return between now and next Sunday is not possible. As such, the Nuggets will be on the hook for his whole season’s salary, purely because of the misfortune of his accident. They can still trade him during the season – and as a luxury tax paying team, they will – yet the necessary inclusion of cash as incentive in the deal will make this accident an expensive one for Denver, and a lucrative one for Brian.

The lesson, as always = only ever get hurt when under contract.

(By the way, Jason Richards was forced to retire due to the injury he suffered. It never properly healed, and after two more significant setbacks, he gave up playing last month to go and work for Pittsburgh as a video co-ordinator. Mike Wilks, however, is fine now.)

|

| Even when drafted, Erick Dampier had a tiny head. |

– The following players have unguaranteed 2010/11 contracts. They are the only ones who do.

Boston – Von Wafer ($150,000 of $854,389 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Boston – Tony Gaffney (none of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $50,000 guaranteed on opening night)

Boston – Oliver Lafayette (none of $762,195 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Charlotte – Erick Dampier (none of $13,078,000 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Charlotte – Derrick Brown ($100,000 of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $200,000 guaranteed on September 1st, becoming fully guaranteed on November 1st)

Cleveland – Danny Green (none of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $125,000 guaranteed on opening night)

Denver – Brian Butch (see above)

Denver – Coby Karl (none of $854,389 guaranteed, becoming fully unguaranteed on August 15th)

Golden State – Jeremy Lin ($350,000 of $473,604 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Golden State – Vernon Goodridge (none of $473,604 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Houston – Alexander Johnson (none of $885,120 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Houston – Mike Harris (none of $854,389 guaranteed, becoming $10,000 guaranteed on August)

Indiana – A.J. Price ($175,000 of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $380,000 guaranteed on opening night, becoming $531,000 guaranteed on December 1st, becoming fully guaranteed on January 5th)

Indiana – Josh McRoberts ($500,000 of $885,120 guaranteed, becoming fully guaranteed on opening night)

L.A. Clippers – Willie Warren ($100,000 of $500,000 guaranteed, becoming fully guaranteed on November 1st)

L.A. Clippers – Marqus Blakely [sic] ($35,000 of $473,604 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Miami – Shavlik Randolph ($250,000 of $992,680 guaranteed, becoming $500,000 guaranteed on opening night)

Miami – Kenny Hasbrouck ($250,000 of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $500,000 guaranteed on opening night)

Milwaukee – Luc Richard Baha Mootay (none of $854,389 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Minnesota – Greg Stiemsma (none of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $100,000 guaranteed on September 15th)

New Jersey – Ben Uzoh ($35,000 of $473,604 guaranteed, becoming fully guaranteed on opening night)

New Jersey – Zoobs ($50,000 of $473,604 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

New Jersey – Sean May (unknown)

Phoenix – Matt Janning (unknown)

Sacramento – Darnell Jackson (none of $854,389 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Sacramento – Donald Sloan ($10,000 of $473,604 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

San Antonio – Curtis Jerrells (none of $762,195 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

San Antonio – Alonzo Gee ($100,000 of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $200,000 guaranteed on November 25th, becoming $300,000 guaranteed on December 20th)

San Antonio – Garrett Temple ($110,000 of $762,195 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Toronto – Joey Dorsey (25% of $854,389 guaranteed, becoming 50% guaranteed on November 1st, becoming fully guaranteed on December 1st)

Toronto – Dwayne Jones (none of $992,680 guaranteed, becoming fully guaranteed on August 15th)

Toronto – Sonny Weems (none of $854,389 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Utah – Sundiata Gaines ($25,000 of $762,195 guaranteed, becoming $50,000 guaranteed on opening night)

Utah – Othyus Jeffers (none of $762,195 guaranteed, no guarantee date)

Utah – Jeremy Evans (unknown)

All but two of those are for the minimum salary. Dampier is the significant one that isn’t, and it is a mere matter of time until Charlotte waives him. (They seem to be waiting to hear about a brilliant deal that Dampier’s contract with facilitate, unaware or unwilling to accept that Dallas would have taken such a deal if it existed.) The other non-minimum, that of Clippers draft pick Willie Warren, is a mere $26,396 above the minimum, and will therefore be treated as one from now on.

The fact that these players are earning the minimum makes it unlikely that they will ever be used as trade bait; although it’s happened before, such as in the trade that took Renaldo Balkman to Denver, it’s more likely that they’ll be used as trade filler, or not traded at all. The latter is the significant favourite there. Use your own discretion as to who will be waived and who won’t, but in some cases (Dampier, Weems, Mbah A Moute, McRoberts), the answer should be pretty obvious.

Of those above players, 14 belong to the aforementioned list of players who signed partway through last season with unguaranteed 2011 salaries as well (see the section about Butch for more on that). Brown, Green and Price are mid-to-late 2009 second-round picks, for whom it is fairly commonplace to have an unguaranteed second season. Mbah A Moute, Jackson and Weems are 2008 second-round picks moving into unguaranteed third years, which is an increasingly common trend. Warren and Evans are 2010 second-round picks, most of whom haven’t signed yet. McRoberts is the rare exception of the player whose second contract has only a partially guaranteed second year. And Dampier signed his deal a hundred million years ago.

That then leaves 11 players whom could be considered as very early 2010 training camp signings; Wafer, Lin, Goodridge, Blakely, Randolph, Hasbrouck, Uzoh, Zoubek, May, Janning and Sloan.

The significance there is that at least 9 of those 11 players have signed training camp contracts that have guaranteed compensation. Janning does, although I don’t know the specifics of it yet; so far, Goodridge is the only that doesn’t. This comes as a direct contrast to last season; despite all of the players who signed for training camp, only seven had any guaranteed money. Those were Sun Yue (Knicks, $10,000), Mike Harris (Thunder, $10,000), Luther Head (Pacers, $250,000), Stephen Graham (Bobcats, $100,000), Trey Gilder (Grizzlies, $25,000), Malik Hairston (Spurs, $50,000) and Curtis Jerrells (Spurs, $75,000). Deron Washington got $250,000, but as a former draft pick of the team who signed him, we’re not counting him. None of the rest of the scores of camp signings had any guaranteed money. Some players like Wesley Matthews and Coby Karl made rosters in spite of this, and some like Derrick Byars and Linton Johnson were waived deliberately late to get them a couple of days worth of money, yet that’s all the money non-draft picks got to go to camp. In only the second week of August, we’ve seen more guaranteed training camp contracts than in the whole of last season.

Perhaps we should cite this as an example of the economic turnaround.

(It’s mystifying how teams can haggle over a few million dollars with their best players, and haggle equally stubbornly over a few thousand for their fringe players. But such is the nature of the business.)

|

| Paul Pierce taking the John Wall to a new level |

– In re-signing for four years and $80 million with the Dallas Mavericks, Dirk Nowitzki was able to secure himself only the second no-trade clause in the league. The other one belongs to Kobe Bryant. Not many players are eligible for no-trade clauses; to be eligible, a player has to have 8 years of NBA experience, at least four years of which have to have been with the team he’s signing with (albeit not necessarily consecutive years). Other eligible players such as Paul Pierce and Tim Duncan could have had them worked into their most recent contracts, but didn’t; then again, they didn’t really need to. They’re not being traded. Not now, not ever.

The other type of no-trade clause – the one made famous by Devean George – involves players on one year contracts who will have early or full Bird rights at the season’s end are given the right to veto any trades that they may be in, so that they aren’t powerless to prevent having their Bird rights taken away from them (which is what happens when such players are traded, for reasons I am not aware of.) The players who qualify for that criteria and thus yield that power are as follows;

1) Jason Collins (Atlanta)

2) Marquis Daniels (Boston)

3) Anthony Carter (Denver)

4) Rasual Butler and Craig Smith (L.A. Clippers)

5) Shannon Brown (L.A. Lakers; this can be avoided if he invokes his player option for next season concurrent to the trade.)

6) Jamaal Magloire and Carlos Arroyo (Miami)

7) Aaron Gray (New Orleans; same as Brown.)

8) Josh Howard (Washington)

Just because they have this power, it doesn’t mean they will use it. Devean George did, but that was the exception; players last year who could have done but didn’t include Nate Robinson and Royal Ivey. Nor did Aaron Gray, who has achieved the unusual feat of having the right to veto a trade in back to back seasons. It is, however, something to note.

– I don’t actually know what happens to Lorenzen Wright’s cap hold after his death. I would have assumed it had disappeared from Cleveland’s cap number, given that it serves no purpose any more. However, as of the time of writing, it has not.

– The Miami Heat’s contract situation now looks like this.

(picture removed)

At the start of free agency, they were projected to have this.

(picture removed)

So how did they go from one to other? With the kind of creative financing that Otis Smith could only dream of. Since several people have asked, there follows an explanation of how Miami managed to get so far below the salary cap, and then so far above it, all in the same offseason. [Note: the renouncements were way more staggered than this, yet that is irrelevant to the wider discussion.]

Miami finished last season with a 16 player roster, due to Rafer Alston being on the suspended list. Of those 16 players, 13 were able to become free agents. And 12 of them did.

Listed in the second picture there are team options for Kenny Hasbrouck and Mario Chalmers, as well as player options for Dwyane Wade and Joel Anthony. Hasbrouck’s option was declined and Chalmers’s was exercised, while Wade and Anthony both opted out. That left Miami with only Chalmers, Michael Beasley, Daequan Cook and James Jones under contract, in addition to the cap hold for their first-round pick.

To free up more space, Miami traded Cook and the pick to Oklahoma City for the #32 pick. First rounders have a cap hold, and second rounders don’t, so with Miami receiving no incoming salary in return, they were able to shed about $4 million from their 2010/11 payroll.

James Jones’s weird contract saw the final three seasons guaranteed for only $1,856,000, $1,984,000 and $2,112,000 respectively, for a total of $5,920,000. If Miami cut him, that’s all they would have owed him, a significantly lesser amounted than the $14,910,000 they would have owed him had they not waived him before July 1st. Miami tried to trade this contract so that they could owe him nothing at all, yet there were no takers, and so they ended up waiving him.

However, rather than paying Jones $5,920,000, they instead paid him only $4,920,000. In a bid to open up more cap room, Miami co-erced Jones into giving up a million dollars of what they owed him; they did this by agreeing to pay him what they owed him in one lump sum. The two most important rules with buyouts are that;

a) the amount of money that the team pays the player is that amount that is charged to the cap,

b) the amount that is charged to the cap is spread evenly amongst all remaining guaranteed compensation on the contract.

However, that doesn’t affect how the money itself is paid out. Players and teams can pretty much do what they want in that regard. Put more simply, what you see on a team’s salary cap chart (such as the one above) is not always what is actually paid out. Jones’s incentive to give up $1 million was to turn three years of small checks into one big fat $5 million one that he could have instantly; Miami’s incentive to cut him that check was to to reduce Jones’s cap hit and open up more cap space. Using rule (a) above – whereby the distribution of the buyout amount must be equal to the distribution of guaranteed compensation in the original contract – Jones’s cap hits became $1,544,172, $1,650,667 and $1,757,161 respectively, thereby opening up $311,828 in 2010 cap room for Miami.

(Shawn Kemp went the other way with his buyout. The Blazers are still paying him, and will be for a few years, yet his cap hit disappeared a long time ago. Kemp sacrificed a significant amount of money in order to leave the Blazers and attempt to resurrect his career, agreeing to take his payout over a much longer period of time. Probably a wise choice, given the younger Shawn’s expensive past. But while he’s on their payroll, sort of, you’ll never again see him on their cap. This is another example of how salary cap numbers and salary paid out don’t necessarily match up.)

After the Jones buyout came their renouncements. With the team option on Mario Chalmers exercised, the team promptly renounced everyone other than Dwyane Wade [sic] and Joel Anthony. This meant that 10 free agents from the previous season were renounced; Jermaine O’Neal, Quentin Richardson, Udonis Haslem, Dorell Wright, Yakhouba Diawara, Rafer Alston, Carlos Arroyo, Jamaal Magloire, Shavlik Randolph and Kenny Hasbrouck. Some free agents from previous seasons were also still clogging up cap space; namely, Alonzo Mourning, Steve Smith, John Wallace, Wang Zhi Zhi, Gary Payton, Bimbo Coles, Christian Laettner, and Shandon Anderson. In total, before these renouncements took place, Miami’s free agent cap holds amounted to a total of $88,184,132, $24,166,800 alone was for Jermaine O’Neal.

(If you don’t know what renouncements or cap holds are, click here. And if you don’t know what they are, well done on making it this far.)

Miami did not renounce Wade because they wanted to keep him (obviously), and they didn’t renounce Anthony because his cap hold was so small. After Anthony opted out, Miami extended him a qualifying offer, which they were perfectly capable of doing since he had only three years experience. You can make any free agents of yours with three years or less experience into restricted free agents, whether they like it or not, by extending a qualifying offer. The only exception is players on rookie scale contracts who had options declined, but this did not apply here. (Kenny Hasbrouck was also eligible for a qualifying offer, but did not get one.) Anthony’s QO was equal to the minimum salary plus $175,000 (a total of $1,029,389), and his cap hold was equal to his qualifying offer. So after all the renouncements and options and buyouts and qualifying offers and trades and stuff, Miami then found themselves in this position;

Dwyane Wade [sic] – $16,568,908 (cap hold)

Michael Beasley – $4,962,240

James Jones – $1,544,172 (waived)

Joel Anthony – $1,029,389 (cap hold)

Mario Chalmers – $854,389

Eight roster charges = $473,604 * 8 = $3,788,832

Total = $28,747,920

At that point, Chris Bosh agreed to join the team, concurrent with Dwyane Wade’s decision to re-sign. LeBron James then spent an hour the following afternoon wanking himself off on international television over thoughts of his own greatness, inventing a new metaphor for wanking in the process, and while simultaneously committing to joining the Heat. At that point, Miami needed to open up even more cap room.

Even though Pat Riley said it wouldn’t happen, Miami pawned off Beasley to Minnesota in exchange for the Timberwolves’s 2011 and 2014 second-round draft picks. [David Kahn might not have a plan, but he’s made two unbelievable steals in the last two years that are in danger of going overlooked. This was one of them. More of the other in another post.] Subtracting Beasley’s salary and adding one more cap hold put the Heat’s total salary number at $24,259,284, cap room of $33,784,716. Wade then re-signed to a less-than-maximum contract, which started at $14,200,000 and paying $107,565,000 over the full six seasons; for reference’s sake, this is over $16 million less than Joe Johnson got from Atlanta. (This is also the only time Joe Johnson will ever get mentioned in a “creative” financing post. Nothing creative about that contract.) Sign and trades for Bosh and James were then completed, both players signing identical $109,837,500 contracts starting at $14,500,000.

This left Miami here:

LeBron James – $14,500,000

Chris Bosh – $14,500,000

Dwyane Wade – $14,200,000

James Jones – $1,544,172 (waived)

Joel Anthony – $1,029,389 (cap hold)

Mario Chalmers – $854,389

Seven roster charges = $473,604 * 7 = $3,315,228

= $49,943,178

= $8,100,822 in cap room.

Miami then signed Mike Miller, prioritising – rightly – their backup swingman spots before addressing their massive holes at point guard and centre. Miller signed a five year, $29 million deal starting at exactly $5,000,000; the addition of his salary, plus the removal of one roster charge, left the Heat with $3,574,426 in cap room.

To facilitate all this, Udonis Haslem had had to be renounced. So in order to keep him, as they so badly wanted to, Miami had to use that space on him. As was the case with the big three, it involved Haslem taking a discounted contract that was below his market value, yet with the incentive of the stars around him, maximum raises and a big arse trade kicker (more on that later), Haslem was persuaded to do so. He signed a five year deal starting at $3,500,000, using up the last of Miami’s cap space in doing so. And they still only had six players under contract.

(Miami used the last dreg of their cap space to sign 2010 second-round draft pick Dexter Pittman to a three year minimum salary contract; the Minimum Salary Exception only lets you sign players to the minimum for up to two years, so the Heat had to use cap room to get Pittman his three years. His contract, starting at the rookie minimum of $473,604, used up the final dollop.)

Joel Anthony’s contract did not require cap space. Because Anthony had spent three years with the Heat without changing teams as a free agent, he was a “qualifying veteran free agent” – a lawyerish way of saying they had full Bird rights on him. As such, they could re-sign Anthony for whatever they wanted using the Larry Bird exception, and did so when they re-signed him to a five year, $18,250,000 contract after the Haslem deal was closed. His cap hold was incredibly small, and he’s BYC because of the big jump in his salary, yet there was nothing untoward behind how they were able to sign him. It was all a very well planned and timed case of creative financing. (Why they gave $18 million to a 28 year old who averages 2/2 and who is both a poor scorer and rebounder is not immediately obvious – his defence isn’t THAT good – yet we’ll overlook that for now.)

Miami have since signed nine other players; free agents James Jones (again), Shavlik Randolph (again), Kenny Hasbrouck (again), Carlos Arroyo (again), Jamaal Magloire (again), Zydrunas Ilgauskas, Eddie House and Juwan Howard, along with second-round draft pick Patrick Beverley (2009). All but two of those contracts are fully unguaranteed in 2010/11; the only two that aren’t are those of Randolph and Hasbrouck, both of whom are $250,000 guaranteed. Miami signed these players using the Minimum Salary Exception, a simple and oft-used exception that allows over-the-cap teams to sign anyone to a minimum salary deal for either one or two seasons. (To sign someone to the minimum for more than two years requires either cap space or a chunk of a suitable exception; since Miami didn’t have an MLE or DPE or anything, this is why they used their last dollop of cap space on Pittman.) These final signings have given Miami a roster of 17 and a salary cap number of $68,340,295; from having less than $4 million committed at one point, they are now less than $2 million below the luxury tax threshold.

So, that’s how Miami managed to simultaneously clear as-near-as-is their entire cap and approach the luxury tax barrier in the same season. Reliant on discounts it may have been; it was still creative, and it was definitely financing. You will probably never see this again.

(Additionally, it is quite irritating quite how many people have come out and commented about how Miami hasn’t won anything yet, the latest being Robert Parish. It’s an automatic and logical reaction any time anyone ever puts together a title contender; to shoot them down straight away and downplay what’s on paper by highlighting that nothing has been translated onto the court yet. It’s true, they haven’t won anything yet. They aren’t defaulted a championship just because of what they did in free agency. They haven’t won anything. They might not win anything. And if they don’t, it’s their own bloody fault. But let’s not be contrarian for the sake of being contrarian. The Miami Heat absolutely killed it in free agency. Apart from their bizarre love for Joel Anthony, they went out and put together what should in theory be the almost perfect team, a series of quality pieces for a series of quality prices. They got everything they wanted; they got everything everyone wanted. They destroyed the field. They won the battle by so far that there’s no point even remembering who won the silver medal. They Usain Bolted this competitive 2010 free agency period and made it not competitive at all. As much as we might want to piss on those chips, we can’t. Not until they lose something.)

|

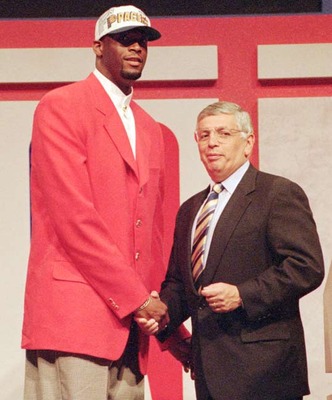

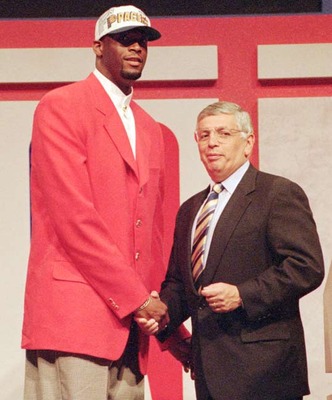

| This picture is rather old. |

– Inspired by the above, and because it’s fun, here’s a list of players who were renounced by teams with cap space this offseason.

Chicago – Brad Miller, Acie Law, Joe Alexander, Jannero Pargo, Ronald Murray and Devin Brown.

L.A. Clippers – Steve Blake, Travis Outlaw, Mardy Collins, Drew Gooden, Steve Novak, Bobby Brown and Brian Skinner.

Miami – Jermaine O’Neal, Quentin Richardson, Udonis Haslem, Dorell Wright, Alonzo Mourning, Yakhouba Diawara, Rafer Alston, Shandon Anderson, Carlos Arroyo, Bimbo Coles, Christian Laettner, Jamaal Magloire, Gary Payton, Shavlik Randolph, Steve Smith, John Wallace, Wang Zhi Zhi and Kenny Hasbrouck. (Hasbrouck, Randolph, Magloire, Haslem and Arroyo later re-signed anyway.)

Minnesota – Latrell Sprewell, Darko Milicic, Damien Wilkins, Kirk Snyder, Michael Doleac, Oleksiy Pecherov, Sasha Pavlovic, Brian Cardinal, Sam Jacobsen, Nathan Jawai, Oliver Miller, Sam Mitchell, Andrae Patterson and Bracey Wright.

New Jersey – Bobby Simmons, Tony Battie, Trenton Hassell, Josh Boone, Bostjan Nachbar, Chris Quinn, Maurice Ager, Darrell Armstrong, Travis Best, Rodney Buford, Hubert Davis, Sherman Douglas, Jack Haley, Donny Marshall, Gheorghe Muresan, Jabari Smith, John Thomas and Derrick Zimmerman.

New York – Tracy McGrady, Al Harrington, Chris Duhon, Eddie House, Sergio Rodriguez, Jonathan Bender, Kelvin Cato, Andrew Lang, Larry Robinson, Felton Spencer, Bruno Sundov and Qyntel Woods.

Oklahoma City – Etan Thomas.

Washington – Josh Howard, Mike Miller, Randy Foye, Javaris Crittenton, Anthony Peeler, Earl Boykins, James Singleton and Chris Whitney.

Teams with cap space didn’t necessarily renounce everybody, though. Chicago still have a cap hold on Martynas Andriuskevicius, as do New Jersey with Jarvis Hayes, as do New York with J.R. Giddens and Earl Barron, as do Oklahoma City with Kevin Ollie and Mustafa Shakur, as do Sacramento with Ime Udoka, and as do Washington with Fabricio Oberto, Cartier Martin and Cedric Jackson. Teams don’t normally renounce these cap holds until they need to, and none of those teams used enough cap space to need to open up every last drop of it. Of course, neither did Minnesota, who nevertheless went ahead and renounced everyone anyway.

A full list of current free agent amounts, along with an explanation of what you can do with them (and also how to get rid of them), can be found here.

|

| “Elevate,” it says, next to a picture of Matt Carroll. |

– The magical, mystical, my-God-this-is-such-a-unique-contract-and-a-history-making-trade-chip Erick Dampier unguaranteed contract DUST chip thing – I hate unnecessarily abbreviations almost as much as I like hearing myself talk – was used last month in an underwhelming trade that brought Tyson Chandler to Dallas, while sending the non-expiring contracts of Matt Carroll and Eduardo Najera the other way. Bizarrely, Charlotte preferred this Chandler deal to a prospective one that would have sent him to Toronto, even though this trade saw them taking on significant salary for players they won’t (or shouldn’t) play. John Hollinger summed up the deal thusly:

I’d like to congratulate Michael Jordan on being the first executive in history to avoid saving money in a salary dump. Tyson Chandler and Alexis Ajinca have one year left at a combined $14.1 million, while Eduardo Najera and Matt Carroll are owed a combined $17.1 million over the next three years. Throw in cash (presumably the maximum allowable $3 million) from Dallas, and they managed to break even while giving away their starting center for two guys who will occupy seats 11 and 12 at the end of the bench. Strike up the band.

Sacramento once did something similar when they took on salary to save money; at the 2009 trade deadline, they took on the 2012 expiring salary of Andres Nocioni in exchange for the 2010 expiring ones of John Salmons and Brad Miller, just so that they could get Drew Gooden’s 2009 expiring back. However, they gained cap space out of their deal. Charlotte haven’t. Until such time as they waive Dampier, they’re going to be over the luxury tax threshold, a team that just sold for half of what the Warriors did, with only one playoff appearance in their history, a coach who doesn’t really want to be there, and little youth around which to restart. Expansion wasn’t the problem; mismanagement was, as was clogging the cap with unnecessary contracts to marginal players (one of which was the Carroll contract, which they are now again stuck with.) This trade bought them some wiggle room over the next twelve months, but only at the expense of less wiggle room in the 12 months after that.

A better way to save on salary is to stop taking on crap contracts.

|

| Dork Elvis |

– Because of the 2010 free agency bonanza, there’s considerably more teams with cap relief than there are teams that need it. This is a far cry from the usual fare, where many teams have to bite the bullet and pay some tax, because there aren’t enough teams able to take on their excess salary (nor enough dead salary to dump). Oklahoma City were the beneficiaries of this system last year when they took on Matt Harpring’s dead weight contract from Utah, receiving Eric Maynor as the sweetening incentive for doing so. Oklahoma City also did a similar deal on draft night when they agreed to take on Mo Peterson’s deadweight salary from New Orleans as a vehicle for obtaining Cole Aldrich’s draft rights; in return, they sent the #21 and #26 picks the other way.

In making that trade, the Thunder took themselves out of the free agency running. Their cap space, which could have otherwise been significant, was bludgeoned to a dollop by the presence of Peterson’s redundant post-trade kicker salary of $6,665,000, money which could otherwise have been spent on free agents. Of course, the Thunder knew this in advance, and did the deal anyway. They clearly felt that Aldrich was a better player and a better fit than anyone they could realistically land in free agency.

Based on what transpired, they were right. Three of the biggest free agents landed in Miami. Three more re-signed. David Lee went to a team without cap space. New York and Chicago bagged only one each; New Jersey, L.A. Clippers, Sacramento and Minnesota came away with none. There remain very few decent free agents now – Louis Amundson excepted – and yet some teams out there still have money to spend without anyone to spend it on.

Since so many teams had so much cap space, only to strike out, some of that cap space still remains. There also exist some TPE’s, a list of which can be found on this website. (It’s slow to update, however.) With the market largely bereft of multi-year contract candidates,, teams might now have to use that cap space via trade. Just like Oklahoma City did.

There’s not a whole lot of luxury tax-paying teams out there. Or rather, to rephrase that; there’s not a whole lot of teams out there who are threatened by the luxury tax and looking to make moves to get under it (like New Orleans were with the Aldrich deal). Most of the tax paying teams are there on purpose. Yet there exist some teams that both want and need to dump salary in ways which, if you think about them enough, are entirely predictable. Maybe not the specifics, but the general idea.

The teams projected to be over the $70,307,000 luxury tax threshold in 2010 include Boston ($77.8 million, assuming Sheed got nothing), Dallas ($84.5 million), Denver $83.8 million), Houston ($73.6 million after the Trevor Ariza/Courtney Lee trade), the L.A. Lakers ($91.9 million before Shannon Brown), Orlando ($92.6 million), Portland ($72.8 million) and Utah ($75.3 million). Some of those teams will never get under the tax threshold, and some of them won’t try. But some will, and even those that don’t make it will probably pawn off excess salary onto the teams with cap space they’re otherwise struggling to use. Here are some such dumps that I’m officially predicting, apart from the ones that I’m not.

1) Sasha Vujacic

– Called it early in this long piece which is now no longer relevant; a few days after that was written, the concurrent story broke. It makes sense; L.A. has a crapload of salary committed, yet apart from the contracts of Vujacic and Luke Walton, it is all committed on purpose, i.e. spent on the rotation players that have seen them win back to back championships. Walton’s three year contract would be the one they’d rather dump, but because of its length (and the fact that Walton will probably miss next season), it’s the one that can’t be shifted right now. So for the sacrifice of a first-round pick – which would only otherwise be spent on a player who wouldn’t play, if not sold outright – the Lakers can move Vujacic. This is the kind of deal that Minnesota or Sacramento should look to do. After all, it’s basically a free pick. Don’t expect it until the deadline, however.

2) DeShawn Stevenson

– Similar to L.A, Dallas has huge amounts of salary committed, but it’s mostly to worthwhile players. After dumping Eduardo Najera and Matt Carroll off to Charlotte, DeShawn Stevenson remains their last dead salary, a $4.1 million expiring for an excess guard who figures not to see a minute behind Jason Kidd, Jason Terry, Jason Barea, Jason Butler, Jason Beaubois and Dominique Jason. Trading Stevenson doesn’t get Dallas out from the luxury tax – nothing feasible ever will. But if that bothered them, they wouldn’t have traded for Jason Chandler. Even with their willingness to pay the tax, though, they’ll only pay it for players who are worth it. Since Stevenson isn’t, he represents easily trimmable fat, just like Shawne Williams was last season. If Stevenson gets paired with a 2011 first, he’ll make a good backup free-pick plan for whoever doesn’t get Vujacic. Dallas can always buy another one.

3) Jared Jeffries or Chuck Hayes or something (although probably Jeffries)

– Before yesterday’s four way trade that saw them move Trevor Ariza for Courtney Lee, and before the dump of David Andersen onto Toronto, Houston were about $10 million over the luxury tax threshold. After those moves, they’re now about $3.2 million over it. They also currently have 16 players, eight of whom are big men, and only two of whom can play point guard. The unguaranteed contracts of Mike Harris and Alexander Johnson are easy enough to cut, yet they save only $1.7 million and are not enough to get Houston under the luxury tax. Cutting those two, as well as trading Chuck Hayes for no returning salary, would achieve this. Yet Hayes has done nothing to deserve to be salary dumped; at $2 million for one season, he represents good value for the amount he contributes. Jeffries’s $6.8 million expiring will be harder to dump, but it’s possible; pairing him with a pick like above and sending him to Sacramento or Washington, or trading him with sweetener (maybe Jermaine Taylor, who was just made redundant by Lee’s arrival) to Minnesota for Sebastian Telfair, are all possibilities.

4) C.J. Miles, or Ronnie Price, or both

– In spite of it all, Utah are still over the tax. Trying to get under it has cost them Ronnie Brewer, Eric Maynor and Wesley Matthews, and yet they’re still $5 million over it. To get under it this year, they could dump the above two, yet Miles is a good two-way player on a decidedly reasonable contract. They don’t want to just have to dump him. Doing so would leave only Othyus Jeffers and Raja Bell at the two guard spot, which isn’t really sufficient, and it’d mean losing a young contributor. Even if they get a first-round pick for him, it’ll smart. But if there’s another way to get under the tax, I don’t see it. As much as it might be preferable to trade Andrei Kirilenko somewhere – especially since he’s bolting for New Jersey next offseason – it won’t be easy. $17.8 million contracts are not easy to deal. This, then, puts Miles on the hot seat.

The only question is how much of a priority Utah puts on dodging the luxury tax. Based on last year, it’s quite a lot.

5) Brian Butch

– See above for why. As for where……he’s earning the minimum. Pretty much anywhere can take him.

6) Renaldo Balkman

– Denver’s paying tax unless they can salary dump Kenyon Martin. Since they can’t, they’re paying tax. They did so last year as well, and yet they didn’t let this prevent them from giving Al Harrington the full MLE this summer, so it obviously didn’t bother them too much. However, Harrington’s contract, as well as the position he plays, should be the death knell for Renaldo Balkman. Balkman is under contract for three more years at an entirely reasonable $1,675,000 per annum, but he played only 13 games and 91 minutes for Denver all last year. And while a back injury was partly responsible for that, the majority of it was done via DNP-CD’s and trips to the inactive list. With Harrington now ahead of him, forward minutes just became even harder to find, and Balkman became even more surplus to requirements. Nonetheless, Balkman fits a need on many teams and should be relatively easy to trade at that price. He makes sense in Washington, for example.

7) Joel Przybilla

– It’s not that Przybilla can’t play. He can. Przybilla has been a good player ever since he learnt to gets his rebounds per game average above his fouls per game average, and after six years with them, Portland know that as well as anyone. However, Przybilla is recovering from a broken kneecap, and while he aims to return for opening night, it might be a tough ask. And when Portland return to full health, Przybilla is struggling to find a role. With Greg Oden and Marcus Camby on board, and assuming both are fully healthy – an ambitious ask for both of them – Przybilla has no role to fit. It’d be great to keep him anyway, since you can never have enough quality size, particularly when you have such health concerns amongst your big men. However, Portland are also $2.4 million over the luxury tax threshold, even before Patty Mills signs. Prizz, as the non-core luxury excess veteran player thing, is the obvious candidate to be moved to help get them under it. How much money they can take back is dependent on whether the Blazers finally concede that Chicago’s offer of a future first-round pick for Moody Fernandez is more than fair. (Which it is. But hey, if you want to keep him and see his value get any lower, be my guest.)

8) Something from Orlando

– Orlando has a $92 million payroll because the father of creative financing, Otis Smith, can’t creative finance to save his life. The Magic’s ownership just keep cutting him bigger and bigger checks, letting him sign and retain whoever he wants and whatever the cost is. It’s kind of ludicrous, yet such generosity has allowed the Magic to assemble a competitive team, more with financial muscle than craft. (If you’re a Magic fan who doesn’t thank ownership every day for this, there’s something wrong with you. Organisations win championships.) However, is there a limit to this spending? By matching Chicago’s offer sheet to J.J. Redick, Orlando will be CTCing for $15 million this year just on Redick, after the luxury tax and signing bonus are taken into account; all that for a backup shooting guard. Was that the final straw?

If it wasn’t, perhaps it should have been.

|

| Apropos of nothing, here’s a vexed Jon Scheyer |

– A recent post listed all unused trade kickers in the NBA at that moment, which you may or may not have been interested in. In light of this offseason’s transactions so far, that list now needs updating.

Since the last list was written, Mo Peterson, James Posey, Charlie Bell, Hedo Turkoglu (amazingly) and Samuel Dalembert have all been traded, exercising their trade kickers. Roger Mason Jr’s contract expired, nullifying his. Rasheed Wallace retired. LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, Paul Pierce, Shannon Brown and Amar’e Stoudemire have all opted out of their contracts that contained them; James Jones was bought out of his. New contracts for James, Wade, Chris Bosh, Eddie House Amir Johnson, Ray Allen, Udonis Haslem, Mike Miller, Jermaine O’Neal and Quentin Richardson all have trade kickers in, and the updated list now reads as follows.

– Ray Allen (15%)

– Carmelo Anthony (lesser of 5% or $1 million)

– Ron Artest (15%)

– Andrea Bargnani (5%)

– Kobe Bryant (10%)

– Chris Bosh (15%)

– Jose Calderon (10%)

– Eddy Curry (greater of 15% or $5 million)

– Tim Duncan (15%)

– Jeff Foster (lesser of 15% or $1 million)

– Pau Gasol (15%)

– Manu Ginobili (5%)

– Udonis Haslem (15%)

– Eddie House (15%)

– LeBron James (15%)

– Amir Johnson (5%)

– Chris Kaman (lesser of 15% or $4 million)

– Shawn Marion (15%)

– Antonio McDyess (10%)

– Mike Miller (15%)

– Yao Ming (15%)

– Jermaine O’Neal (7.5%)

– Chris Paul (15%)

– Joel Przybilla (15%)

– Quentin Richardson (15%)

– Brandon Roy (lesser of 15% or $4 million)

– Josh Smith (15%)

– Peja Stojakovic (10%)

– Anderson Varejao (5%)

– Dwyane Wade (15%)

– Luke Walton (7.5%)

Six of those players were signees of the Heat this summer. You can probably see what they were doing there.

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/17380243/20130304_ajw_ak9_524.0.jpg) |

| Al Harrington, still not looking as dumb as he did when he had that mohawk |

– Finally, one final blurb inspired by last year’s post. Regarding Paul Millsap, I wrote this:

The Blazers’ offer sheet to restricted Jazz free agent Paul Millsap was oft described as “toxic”. The four year offer sheet started at $7,692,932 – which represents every last dollar that Portland had under the salary cap – before dipping to an even $7,600,000 in the second year. The final two years were for $8,103,435 and $8,603,633 respectively, bringing the contract’s total worth to an even $32 million.

Furthermore, the Blazers did something fairly rare when they included a maximum 17.5% signing bonus into the contract; put simply, this means that Millsap receives 17.5% ($5.6 million) of the entire value of the contract up front. They did this so that it might deter the Jazz (pressed financially this season) not to match it. But ballsily, they did so. And doing so will work in their favour in the long run; for the next three seasons of his deal, whichever team owns Millsap will have $1.4 million less in obligations to pay him than his listed salary will indicate. If ever they decide to trade him, this will be a welcome reprive for the recipient team.

You probably knew all that, but there it is again anyway.

This year, a GM-less Blazers did it again. They signed another Utah restricted free agent (this time, Wesley Matthews) to a frontloaded offer sheet they were hoping the tax threatened Jazz wouldn’t match. And this time, it worked.

Matthews’s new contract calls for the following cap numbers:

2010-11: $5,765,000

2011-12: $6,135,160

2012-13: $6,505,320

2013-14: $6,875,480

2014-15: $7,245,640

Keen mathematicians and idiot savants the world over will notice that even though that contract starts at the value of the full MLE, it is not worth the full value of the full MLE throughout the life of the contract. The full five year MLE, as evidenced in the contract of Al Harrington, is worth $33,437,000: Matthews’s totals only $32,526,600, $910,400 less.

But regardless of that, Matthews has full maximum increases in his contract. His deal contains a $5,690,000 signing bonus, which is a mere $2,155 below the maximum allowable 17.5% signing bonus. Matthews’s contract is 100% guaranteed in every season with no option years; as such, the signing bonus is added to the cap by the symmetrical amount of 20% each season ($1,138,000). With that amount now paid up front, Matthews will now actually get the following annual salaries:

2010-11: $4,627,000

2011-12: $4,997,160

2012-13: $6,505,320

2013-14: $6,875,480

2014-15: $7,245,640

Notice that the 2011-12 salary is 108% of the 2010-11 salary, and thus Matthews is the getting salary possible after his signing bonus is accounted for. The first set of numbers, however, are how he will appear on the cap for whichever team owns him. Portland did pretty much the exact same thing to Utah this offseason that they did last year, and this time, it worked.

Jazz fans should be worried about Sundiata Gaines’s next contract.

It’s impossible to get a job in the NBA as a numbers guy unless you have a law degree. But I’ll keep trying.

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/17380243/20130304_ajw_ak9_524.0.jpg)